One by one, like toy soldiers, we were guided out of the chemistry laboratory. The scent of ammonia stabbed our nostrils to our brains. Our hands were still tingling with the ghosts of the experiments done when the assembly bell tore through the nightmare the chemistry department just showed us could be had anytime and anywhere. An assembly bell at the forbidden hour of eleven had never been heard of in Chianda, but we did not pause to question it. There was no need. We all knew.

For weeks, the truth had been slithering into consciousness. It was creeping through the hallways of our minds like a slow creeping tide. The tables in the library always had newspapers out talking about it.

We heard about it in the hushed, fractured voices of teachers who ritualised telling us the numbers. The ever-rising numbers of infections, deaths, and quarantined individuals of a world crumbling in on itself. The virus no longer was a distant spectre, but the dark cloud s gathering on our throats, a lull before the storm. In our heads, the world was ending. Not in chaos and explosions but in silence and the crunching of numbers.

And the bell, that singular shrill note slicing through the fabled illusion of normalcy. It marked the beginning of an unprecedented inevitable, a harbinger of endings. Deep in our hearts, we knew time was the weight unspeakingly falling apart our world and we could only remain at the edge staring into the void where our ancestry lay. We knew there was no way of averting the storm that faced us. No miracles. Just the creeping dread that the stabbing, the ringing, the gathering, and the moment were the beginning of the end.

The Director of Studies came forward, his proportions cleaving the murmuring community like an ominous shadow into the morning light. His brown trousers hung loose, hollow from the guillotine of his words. He wore the visage of gravity, and the weight that made his frame unable to move. Etched with lines that told about more than just fatigue but of a man forced to swallow the future whole just to exhale it into the ears of children.

He held the microphone firm into his hand as if to brace against the tremor that was history itself. And he exhaled the inevitable decree. Schools would close indefinitely. The statement hung on the atmosphere like an unwanted curtain.

A ripple passed through the assembly. Some faces collapsed into grief privately, others lit up with the brief, feverish joy of an unrequested but dearly welcomed freedom. Beneath it thick and loud knocked the unrestrained yet unbearable truth that nothing would never be as before. There would be no more stories, our world had now tilted over and we all fell into the world of oblivion.

The next morning

We packed our stuff. Unlike other last school days, there was no laughter. Only the silent, frantic urgency of creatures returning to their dens before the storm hit. We didn’t know if we would see each other again as we left with heavy steps towards the gate. Steps of individuals who believed that home was now a fortress before the world turned to ash. That awful ambiguity loomed over our clean-shaven heads like a shroud we could not shake off.

The next morning, we packed our stuff. Unlike other last school days, there was no laughter. Only the silent, frantic urgency of creatures returning to their dens before the storm hit. We didn’t know if we would see each other again as we left with heavy steps towards the gate. Steps of individuals who believed that home was now a fortress before the world turned to ash. That awful ambiguity loomed over our clean-shaven heads like a shroud we could not shake off.

I had steeled myself for an apocalypse. Houses looked as though they had been bombed by the plague with all their window coverings pulled down. Families swaddled in gas masks, eyes wide and wary as alchemists handling the Black Death. Reality, that stubborn but patient force of nature refused to perform my dread. In my estate, life unspooled almost ordinarily save for the occasional sight of the boys in Subarus drifting through the streets like wolves in uniform. Their hungry eyes prying for those whose pockets might fund their supper for not wearing face masks. Far worse was being caught past curfew when they would have to measure authority in the hardness of their knuckles and justice in the cuts and bruises they left behind.

As days bled into weeks, it revealed that we were not the doomed generation as we had believed in school. The terror festered into our minds, fed on scraps of rumour and half-truths and bore children, but was now withering under the slow, steady light of clearer knowledge. The world may have been wounded but was not lifeless. Then came the announcement from Professor George Magoha (the Minister of Education), his voice firm, as a chiselled stone that schools would reopen in January. I had nine months of reprieve; of borrowed time to sharpen my mind like a katana sword before the final reckoning of KCSE.

The relief had a heartbeat inside me, a fluttering pulse of possibility. I allowed myself a single breath, a single suspended moment of gratitude before turning my gaze forward. Next week books would open, pens would flow, and the future would be etched one page at a time into something I could feel in my hands. For five months, I held onto the delusion of studying as if it was a sacred obligation, promising myself that tomorrow would be the d ay. I whispered it would be the day, books would open and pens move, the day discipline would strike like lightning, set my soul on fire and ignite my intentions. Again, reality showed me the truth was softer, slower, and insidious. It slid through my fingers like butter through the fingers of hell, leaving a greasy residue of regret.

On a dusty Monday afternoon, the Cabinet Secretary once again took over the tv, his voice crackling through the static to say form fours would need to return to school the following Monday. With a single statement, he killed and buried the fantasy of endless time. Five months had ended, but I had nothing to show for them, nothing but the ghost of good intentions. That fickle, merciless thing called time had called my bluff, and all my books sat pristine with unbroken spines, and the notes I meant to take only existed in future tense.

A week was nothing but a handful of sand tossed at the mountain of all I had left unlearned, a revolver against the nuke of all I had forgotten. My untouched books stared at me with pity, their pages heavy with four years’ worth of knowledge. The clock’s ticking now thundered in my ears like Thor’s hammer.

I did not dare study

What was the use when the syllabus sprawled before me like an unconquered continent. We only had 7 months to compress the entirety of secondary school education into our minds, some of which had gone through plenty during the holiday. Seven months to understand what should have been absorbed over the course of four years was absurd and almost laughable. Almost.

So, I waited. Deep down, I knew that fate favours the prepared. I didn’t know if I would be prepared enough in time, but I knew all I had to do was start. The rest was useless.

The first night was a cathedral of silence, a silence heavy, reverent, and thick with unspoken understanding. My deskmate, usually quick with a joke, sat hunched over his huge books like a man clinging to a raft. His brother had his head crushed by a falling concrete electric pole during the holidays, and now, being the eldest and the only son, the weight of an entire family’s hope pressed down on his shoulders. Every question he answered, every page he memorized, was a fist raised against a future that had already taken too much away from him.

Another friend of mine had spent those months in the wreckage of a fractured home. His drunkard father may not be around to beat his mother anymore, but his absence could be felt, not in a good way, but it was felt. He was not around anymore to tell him that at the end, he would undoubtedly fail his national exams and would join them in making jikos in town. (Jiko’s are ceramic stoves used to make chapati’s, samosas and traditional pastries). His mother’s quiet strength was the only glue in that household, selling vegetables to support the family of four. For my friend, school was more than just a classroom. It was an escape ladder out of the abyss.

Humans are only creatures of habit, and fear can also grip us so tightly before we betray ourselves back into the familiar. Within days, the silence broke. The nights bloomed again and whispered stories accompanied by muffled laughter and rhythmic breathing of future men who had once more surrendered to sleep in the middle of preps. The urgency that just days earlier had crackled through the air like lightning had faded into the ground and had been replaced by the same old comforting embrace of procrastination.

And only then was I able to see it to see the divide. Some of us were actually fighting for something. For families, for pride, for respect. For futures that had to be conquered because being at the mercy of the future was an unthinkable alternative. Others, on the other hand, had already made peace with the drift.

A week passed, and the numbers glared back at me from the paper, 13% was my cruel verdict, dressed in red. A week later, as if to tell me that my understanding was not just stagnant but retreating. The teachers had their brows furrowed, not in anger but in dread. Dread that if I, once counted among the surest, was floundering like this, what did the future have in store for the rest? They could only imagine the failure waiting for us in April, waiting to sink its poisonous fangs into our futures.

For someone to know how to defeat something else, they must first know how to defeat themselves. So I waged war against my limits. Alarms at 4 AM. Midnight oil burned like I was a Saudi Prince. Three hours of sleep, never enough but just sufficient to keep my body from collapsing. I became a ghost in daylight with my face always buried in books, even as laughter and shouts from the field drifted through the windows. While others ran around, I familiarised myself with content to the desperate hope that effort could outpace time.

In the six weeks that followed, my life was a pendulum. A pendulum swinging between exhaustion and determination, but the determination was strong enough to numb the exhaustion that only compounded in me. Each day was a duel at the precipice of fatigue. Then there came midterm exams, the reckoning.

I wondered whether I would be a profitable trader or had merely traded precious sleep for another kind of failure. When the midterm results were released, there were murmurs at the release. I had gotten 73 out of 84 points. Eyebrows were lifted. Mouths were gaped. Whispers coiled around my name like vines of disbelief. Even more surprising were the results of the man from Matangwe who got 76 points. They all wondered how, as if the numbers they heard were a trick of sound. But I knew how. Only the quiet, iron certainty of a warrior who has counted every scar earned in war. They saw the scores, but I knew the cost.

Long nights, aching eyes

Pages of notes etched into memory by the raft of sheer repetition. My mind was a livewire crackling with exhaustion. Every subject mark with my name to it was a step carved into a mountainside through chisels of hours few saw, and even fewer mourned.

When the end term results were out, 76 points were read with my name, and even the teachers paused. Not only was relief held in their gazes but also a flicker of awe. Considering how I scraped numbers that are only written on the backs of football players. I was ready.

All the patience I had in my heart went up in burning white flames in my heart. What was the need for waiting for four more months? Delay would only dull the edge of my focus. Professor Magoha’s calendar meant nothing to the hunger in my veins. The exams could have been placed before me any day, anytime, and I would have seized them like a blade, for I was a weapon that longed to be wielded.

Only after the end of term exams where we were allowed a 2-week holiday. A holiday too brief to be called a respite, too sweet not to ask for more and not long enough to allow me to forget the things I had read. For a few days, the weight of books didn’t press down my jugular, and I was allowed to remember what it meant to simply be. I finally remembered what it felt like to wake up after the sun had risen and to go to bed without battles with equations past midnight. All I had was the golden stretch of hours that belonged to us alone.

Home smelled of unfamiliar things like good food, petrichor (the smell of rain on dry soil), and peaceful family members who had no problem watching you doing nothing. And I did it well. I could almost pretend KCSE did not exist. Almost. But beneath the calm, tension thrummed its strings, singing me a song about the borrowing of every laugh and the stolen luxury of every lazy afternoon.

Soon, the gates opened again. They opened one last time. This time, there would be no turning back, no room for error, no mistakes because that would mean the four years of struggle and a pandemic were all for nothing.

As expected, the third term arrived, and with it, scrawled countdowns on the whiteboards. Countdown of numbers shrinking like sand in an hourglass. For some, the air felt different. For others, it was just a normal term for they didn’t seem to care much.

In the second term, the winds that caressed our faces carried the crisp of the Lake Victori a, a fleeting coolness to soothe our minds. In the third term, the currents changed. They squeezed themselves through crowded corridors and roads, gathering heat from the bodies of the other classes who joined us until what reached us was a heatwave carrying the scent of sweat, chalk dust, and the metallic tang of nerves.

Despite the countdown. Despite the furnace of urgency around me, my mind still disobeyed me. It refused to catch fire. The gripping discipline I once had was gone. I was no longer able to lose myself in pages for hours. My focus scattered like light on a mirror. The books lay open, but the words were blurred. That wasn’t laziness. It was worse. The weight of the end pressed down on me with the suffocating crush of a tide.

Some people around me marched ahead without hesitation. I held my position, caught between myself and who I had to be. My thoughts raced while I watched the board counts drop off one by one. Every time I held a book, I only saw things I knew and just stopped studying.

The man from Migori

Every assembly was a stage for the Deputy Principal, Mr Nehemiah Ochieng, the man from Migori. He was a stern, clean-shaven titan who was the best orator I had ever met. Rumours had it that his wife used his polished scalp as a mirror. We also heard that before we joined, Mr. Nehemiah Ochieng had once silenced a thunderstorm with a glare. Out of respect, his shadow never moved at noon. He was so tough. Death once had a near-Mr. Nehemiah experience.

There he stood, before rows of uniformed bodies, loading off truths like a man hurling stones into a crowd. Oozing wisdom carelessly. His hands, with the precision of a man who had studied the art of emphasis under history’s most fervent demagogues, slashed through air. The Austrian painter could only dream about gesticulating like our Mr. Nehemiah.

“You walked into those gates alone and marked my words. You shall leave them alone!” He would always thunder. His fingers were always jabbing towards the school gate as if it were the mouth of destiny itself.

The students who weren’t dozing while standing would be suppressing smirks, exchanging sideways glances. It’s like he had not seen brotherhoods forged in the theft of bread from the canteen at midnight. Or the friendships plastered by the cement of shared panic before exams. Maybe he also never saw the love letters smuggled into neighbouring girls’ schools like contraband. In his Adventist eyes, we were solitary soldiers, marching toward individual glory. But what did he know?

Mr. Ochieng’s head gleamed under the Uyoma sun, a mirror not for his wife but for us. Reflecting back to us the solitude we never wanted to acknowledge.

Days dissolved like sugar in hot tea. They were swift, sweet, and gone before I could hold them in my hands. There we were, seven days before KCSE. The air in the classroom was pregnant with a quiet frenzy, the kind that settled when the inevitable too close to outrun.

Chemistry still dangled unfinished. The teacher, Mr. Okal scrambled to stuff final concept s into our minds like overfilled duffel bags threatening to burst open. But at the back of my skull, there was no panic. I had in myself full confidence that the week, together with the free time between exam days, was enough to revise adequately for the exams. Like I always said, I won’t get wrong anything I know.

Once more, the library became my battlefield. Notes from the last 4 years spread across the table. They were easier to go through this time. I drilled them until words echoed in my dreams. Sleep was a luxury and focus, my old friend, a necessity.

The day before the exams began, the principal’s message came wrapped in nobled intentions. It talked of afternoon sessions. A chance for teachers to “echo last lessons” and “of fer predictions.” But we weren’t fools. This was a dance on the edge of rules. You can imagine just how much the crowd rejoiced.

Boys who used their books like pillows and measured lesson times in yawns lit up like the skies of Hiroshima. Their grins stretched wide enough to topple the sun’s position on the sky. One would think they were all given keys to their own kingdoms, and in a way, they had. A kingdom built on predictions and nudges, where the line between luck and cheating blurred like vision under water.

Their euphoria was like the virus, spreading all over. If joy were a currency, theirs could’ve been enough to be divided amongst every soul on earth, and the remainder used to tempt the devil.

And so, we gathered under trees each afternoon. Without failure, the teachers resurrected some of the things they had taught in the four years. They told us some of the questions they were predicting since most of them were markers of KCSE scripts.

The morning of KCSE

The air was thick as I stepped into that classroom on that Friday. Some heads slumped on desks, surrendering to exhaustion. Others, nose deep in notes, cramming four years of learning into four desperate hours. But success, like gold, holds its value only because not everyone finds it. That is why the world cheers when one does find it. They all know what it takes.

At 8 AM, the clock struck zero, and KCSE was no longer something we only ever heard people talking about. It was with us. Its breath was hot on our necks. I felt no flinch when the exam booklet landed on my desk. My hands were steady like a hen’s neck. For four years, I had faced monsters like these. Taunting monsters, monsters that twist the mind, and I had lived to tell the tale. I also remembered our teachers’ words that the government knows the pandemic stole time from us and would be lenient. But fate has a cruel sense of humour.

The questions on that paper laughed in the face of yesterday’s predictions. We had been ambushed.

The days blended together like a series of sunken ships as each prediction sank with the reality of the situation everyone’s eyes were now tuned to. But I stood firm, unshaken. I had prepared myself, and little miscalculations couldn’t touch me. Until Chemistry arrived.

The booklet slid onto my desk with a whisper, innocent like a coiled serpent. I was ready to unleash a storm of knowledge so devastating that the examiner would try to find out who I was. Then I read the questions.

From the first question to the last, I quickly went through the paper. I had consumed old exam papers, dissecting trends and even let my fingers bleed equations and mechanisms. A slow laugh that seemed disbelieving began to erupt from my chest. No, this was not a triumphant laugh. It was darker. It was the laugh of a man who had trained for a sprint and found himself at the edge of a cliff. The invigilator’s eyes darted the room like an arrow, trying to triangulate the origin of the laugh. Suspicion knitting his brow. I wish he knew I was laughing at the sheer, brutal audacity of the paper. If that was my Waterloo, I wondered what fresh hell awaited the rest.

My comrades stole glances, searching for clues on my face only to be met by a smirk. Oh, the irony. I was a statue of calm, screaming inside. Did whoever crafted that monstrosity have children? If they ever found the paper lurking on their kitchen table, would they recognize it? Would they weep for us or just simply shrug and say, “Life isn’t fair “?

The clock ticked as my pen hovered, tying goats to trees and then talking about the tree when asked about a goat. I was ready to make the examiners work for every mark they denied me. Each sentence of mine was a carefully constructed lie, each calculation a shot in the dark. In two hours, I turned the booklet into a graveyard of half-truths. An examiner somewhere would be seated on a table, exhuming them and shaking their heads at the carnage.

The walk to the dining hall that day was unlike any others before. No banter or chest-thumping. Just two hundred and eighty-seven and a half pairs of stunned feet shuffling forward suspended in silence. We were survivors of an invisible massacre, moving forward, and did what we can do, which was to wait. I got my tea and sat quietly under a tree. What else could you do when the world brutally reminds you that some battles are meant to be lost? You sit down and drink your tea.

The teachers sensed something was amiss, and before they could pry the horror from our lips, their phones began to ring. Their colleagues supervising other schools were calling. The reports were all the same that by the 15th minute, pens had stopped moving. Classrooms full of students just… staring. At walls, ceilings, and the cruel irony of a paper that promised fairness and delivered slaughter. The Ministry of Education may call that an exam, but I would call it a scythe, one swung indiscriminately cutting down every stalk in its path.

The next day, the maths paper arrived like a second wave of artillery fire. We had thought the worst had passed. Those were just thoughts. Another battle was lost.

That long week bled out slowly, each exam a fresh bruise. It ended with hope packing its bags and leaving. Now, comrades just wanted to finish and go home to their families for the fire was gone and the fight extinguished.

Probably, in another universe, this was a triumph. In this one, it was just survival. And survival doesn’t need applause, just an ending.

The next week arrived with a twist none of us saw coming. The whispers slithered through the corridors like snakes, hissing of leaked papers. This time, they were not rumours but tangible, smuggled truths. Pictures of papers floated through the school like contraband salvation.

And oh, how those who clutched the stolen goods walked now. Heads high, shoulders squared, mouths curled into the smug certainty of men who had cheated fate. They sauntered with the swagger of victors, already tasting a success they hadn’t earned.

I was a very unlucky man, only the subjects I wasn’t taking were leaking. Answers were memorized in shadowed corners and then regurgitated under the sterile glare of exam hall Iights. The system had broken, and through those cracks, they had slipped through laughing.

The final morning dawned with only thirty of us who were taking computer studies left. Most weren’t hunched over notes. No, they lounged with ease of men who had already secured victory. They spoke about making arrangements with men they trusted. Their confidence had a heartbeat.

By 8 AM, comrades were gathered restless. By nine, the jokes had grown louder. Everything seemed to be funny. Probably, they were excited that they were going to trick fate. 10 AM came nothing. 10:30, still nothing.

The first flicker of unease. Then panic rushed in. They paced under the trees like caged animals with their thumbs jabbing at phones. Eyes darting to every passerby as if the question paper might materialise from thin air. And then, the death knell to proceed to the exam room.

The walk was a funeral march. The mouths that spun tales of A’s were now clamped shut. The bright faces pale. No last-minute saviour. No miracle. It’s just the hard reality of blank booklets enthusiastically waiting to expose the truth.

Maybe they were geniuses and architects, after all. Geniuses of self-deception and architects of their own ruin. Or maybe, just maybe, they should’ve studied.

The final paper ended

We walked out of the exam room with the exhalation of survivors. We moved as a pack to the bus stage as Mr. Nehemiah Ochieng watched. And that was it, the end of the road. Now, all that remained was the wait. There was nothing left to do but live. Live in the limbo between then and now, between the students we were and the strangers we’d become.

At home, I also heard stories of cheating from my friends who were in other schools. They talked so highly about it, as if cheating had morphed into valour. Tales were swapped of invigilators looking the other way , about leaks and buying answers, and even about entire papers memorized before stepping into the exam hall. There I sat, silent. I walked into those halls with nothing but capacity of my mind. There were no gimmicks, no shortcuts, and only the beautiful, ugly, raw truth of what I knew. The others had their results built on lies, and that was like a house built on sand. And when the wind blows, as it always does, what would remain?

That morning was a salad of rain drumming against the iron sheet roof, the air thick with the scent of wet earth and mandazi (a triangular bread, rather like a donut but less sweet). As always, I was lost in the universe of a movie when my phone buzzed. The message that Magoha was about to release our results shattered the illusion of calm in our house.

Professor George Magoha, the man whose name had become synonymous with judgment day, was stepping onto the national stage once more. His stern face and no-nonsense demeanour are ready to dictate futures with a single statement. That aesthetically questionable architect of our fates was just moments away from pulling back the curtains.

I wondered if the results would be a reflection of the sleepless nights. The pages I’d filled even with things I wasn’t sure of?

There he stood, a monolith of authority against a backdrop of national anticipation. He was a colossal presence of authority against anticipation on a national scale. His voice was methodical as he read off the names of the highest performers. I hardly paid any attention to them. My fingers hovered over my phone, ready to punch out the code which would transmit my fate in cold, digital lettering.

“Did he just call out your name?” The question sliced through my trance as my head snapped up. A beat of silence. A rush of blood in my ears. And then the realization that the Owino Version was actually Veron Owino. My phone exploded with sounds, pings, vibrations, and shrill ringing. Excited voices sang out and fingers stabbed at keypads in far off places trying to see how many attempted to get in touch, all asking if I was “Owino Version”.

I had made cheating useless to me. Not out of righteousness but because I had armed myself with something no shortcut could replicate, and that’s knowing.

The news of my friends’ results came like scattered leaves in the wind. Some were bright and golden while others brittle and faded. One had boasted cheating from the very beginning and was now clutching a D like a torn flag of surrender. Maybe he had copied the wrong answers or the right answers to the wrong questions.

The results arrived only bearing index numbers, cold and impartial. No favours or alliances, just the unvarnished truth of what each of us had sewn over four years.

How some bonds shattered under the weight of those numbers. There were those who felt betrayed as if loyalty demanded shared failure. As if stumbling together was the only show for togetherness. But the gates of that school had opened for us all, and we had walked through them side by side only to emerge carrying entirely different fates. Maybe Mr. Nehemiah was a prophet.

How absurdly recent those conversations about when we grow up seem. We talked as if maturity were some distant country we might never reach. And now, the fist of life pounds upon the door, and the foolish trembling creatures that we are can only tremble with our backs against it. Wishing desperately that we had built no doors at all, that no such knocking could ever find us.

High school may have been finished, but the lessons have only just begun. What we decide to do with whatever we get from there. A different kind of hardness now, the relentless march of days that demand more than grades, more than obedience. They demand meaning.

And comes the cruellest jest of all, like a thief in the night. A comrade gone. Just like that. No fanfare, no warning, but the hollow silence where a voice once was. One day, they sit beside you, breathing the same air, and the next, they are but a name whispered in past tense. A memory climbing the stairway to the Man upstairs.

All this is just a road to the true horror that haunts more than death itself. That a meaning less life is worse than a short life. We all should strive to find meaning in the choices we make. Our results were important, but even more important were the choices we made to get there and the choices we made after getting there. Could there be anything more terrifying?

Perhaps, just perhaps, the terror is the point. For in its shadow, we are forced to ask what matters if nothing lasts. And there, in the asking, we may yet find an answer.

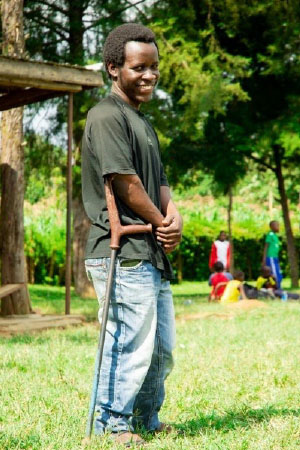

Veron Owino was a student at Chianda High School in March 2020, when all schools in Kenya were closed following the first case of COVID in the country.

In his final Form Four year at the time, Veron and his fellow students returned to school in the October to prepare for their final KCSE exams which were sat in July 2021.

Veron achieved an A- grade in his KCSE which put him in the top 1% of the 745,000 pupils sitting for the exams. He was commended on national television by the Minister of Education, Mr George Magoha.

He is now studying Medicine & Surgery at Masinde Muliro University.